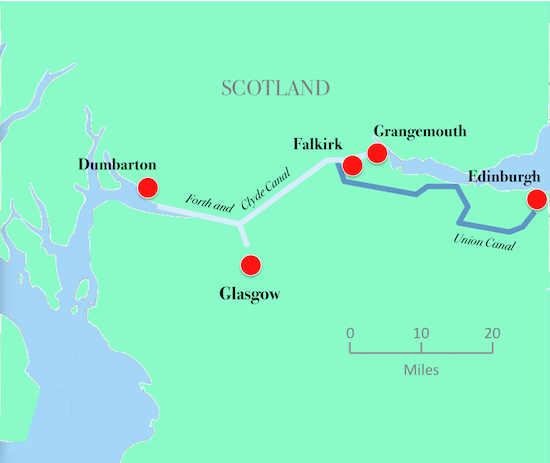

The Union Canal runs for 32 miles from Camelon, near Falkirk, to Tollcross in west Edinburgh. At Falkirk, the spectacular Falkirk Wheel joins the Union Canal to the Forth and Clyde Canal, which runs west to Port Dundas, Glasgow and to Bowling Harbour on the River Clyde near Dumbarton. and east to Grangemouth.

The Union Canal and the Forth and Clyde Canal were built to carry freight in what was then a heavily industrial area. There was a shale oil industry which covered mining, extraction and refining and produced motor spirit. There were mining and quarrying industries. The first detergent washing powder was also manufactured in the canal’s catchment area.

Here’s a map:

The Union Canal took four years to build, opened in 1822, became disused by 1920, closed in 1965 and re-opened to traffic after the completion of renovation work in 2001. Other transport infrastructure was being built in the same corridor at the same time. The railway from Edinburgh to Glasgow via Shotts opened in 1848, and the M8 motorway was built in stages and was completed in 2017.

An unusual feature of the design of the Union Canal, and one which makes it very suitable for passenger traffic, is that it has no locks. The canal follows the level of the 240 ft contour along its entire length. This means that the canal is appreciably longer than the 24¾ mile straight line distance from Camelon to Tollcross, but it is appreciably faster than a canal with locks would have been. Canal locks were a constant source of delay and irritation.

The canal towpath runs along the northern bank of the canal, except for the

stretch that runs through Polmont in tunnel. In the tunnel, the bargee had to lie on his back

on the barge and kick the roof of the tunnel to push the barge through it.

The proposed passenger boat service does not run through Polmont.

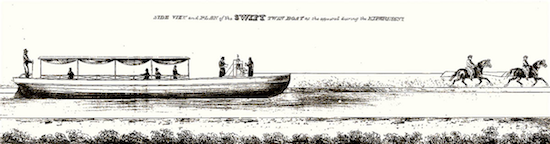

I was moved to put computer, keyboard and mouse together and speculate about restoring a regular passenger service to the Union Canal when I read that ‘Swift Boats’ operated on the Forth and Clyde Canal in its early days and achieved a speed of ten miles per hour (8½ knots), providing a passenger service over the 24¾ miles between Lock Sixteen in Falkirk and Port Dundas in Glasgow at a speed distinctly faster than a stage bus. The Swift Boat service was heavily used, even though the single fare was four shillings (4s) in first class and 2s in second class. (That translates into £14·32 first class and £7·16 second class in today’s money, the first class fare coming remarkably close to the £16 cost of a ticket for a tour bus in Edinburgh today. See here.) The speed of ten miles per hour was achieved by using two horses to haul the boat and changing the horses often. Today the maximum speed of a barge is 4 mph (3½ kn), and Scottish Canals would be unlikely to agree to a higher speed for just one customer. Though, you understand, I’d have to ask.

I was curious to know whether it would be possible to operate a water-bus service on the Union Canal today, starting in Tollcross and conveying passengers ten miles or so to the western suburbs of Edinburgh.

Water bus services in cities, of course, are not particularly unusual. Venice has a whole network of vaporetti where other cities have bus services or trams. London has the Thames Clipper services on the Thames between Chelsea and the O₂ building at Greenwich, as well as a water bus service on the Regents Canal between Little Venice and Camden Lock, operated by the London Waterbus Company.

In Scotland, The North British Railway operated ferries on some lochs to convey passengers from lochside villages to their railway stations. They ceased to operate years ago, but Sweeny’s Cruises still operate a tourist boat service in summer from a boarding point on Loch Lomond.

A waterbus stop on the Union Canalcould be as simple as a sign and a pontoon with mooring posts to enable the bus to stop and board passengers safely. A more elaborate waterbus stop would have lighting and a shelter adequate for Scottish weather conditions. The design has to take into account that a heavily used cycle path runs along the bank of the canal.

In Edinburgh, at the moment, there is no regular passenger boat service on the Union Canal, although numerous passenger boats are available to hire.

Armchair transport engineers, and I include myself, usually delude themselves that it would be possible to operate useful services over any disused railway, footpath or canal that could conceivably be re-opened, refurbished, re-built or re-used, and such services would be so popular among travellers that they would elbow, or if necessary fight, their way on board. If the service were steam hauled, that might even be true. Sadly, though, I had to conclude that in this case, commercial success of a passenger service on the Union Canal between, say, Port Buchan in Broxburn to Edinburgh would be impossible.

First things first, or, Drawing Maps is Fun.

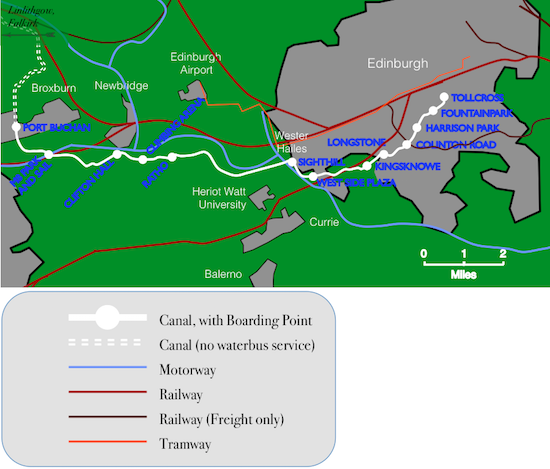

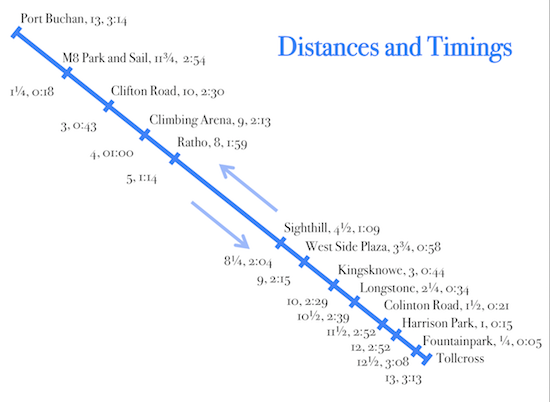

I shall start by showing where the boarding points of the proposed service would be. Here is a map of the Union Canal showing the proposed stopping points. The service starts from the canal basin at Tollcross, on the west side of Edinburgh, and runs westwards to Port Buchan in Broxburn, a distance of thirteen miles. Then it turns round and comes back again. I chose Port Buchan because it is a rather quaint, usable canal wharf in a built up area where some residents might want to commute to Edinburgh, or just ride to Edinburgh for fun on the boat.

The maximum speed limit on the canal is 4 mph and a stop is expected to take three minutes. This includes time for the waterbus to come to a stop, moor at a pontoon waterbus stop, wait for passengers to embark and disembark, and for the waterbus to cast off from the pontoon bus stop and accelerate to the operating speed of 4 mph (3½ Kn.) This includes deceleration and acceleration, but since a passenger carrying vehicle cannot accelerate or decelerate at more than 0·1 g, acceleration from rest to full speed each take about 2 sec., which is regarded as negligible. We can compute journey time as 15 minutes per mile plus 3 minutes per stop.

Waterbus Boarding Points

At the start, I decided to

create an operating timetable which assumed

My first thought was to timetable one waterbus per hour in each direction throughout the

day. The first waterbus eastbound was to leave Port Buchan at 05:00 and the first waterbus

westbound was to leave Tollcross at 05:30. The last

eastbound service was to leave Port Buchan at 21:00,

arriving in Tollcross at a quarter past midnight,

and the last westbound service was to leave

Tollcross at 21:30, arriving in Broxburn just before one o’clock.

There are two

possible standards of viability which could be used.

One is that the whole of the cost of the service should be met from fares.

The other is that one half of the cost should be met from fares and the other half

should come from a government or local council subvention.

The whole of the cost includes salaries, running costs and repayments of loans used

as start-up capital.

The resulting timetable has no chance of being commercially viable,

because the journey times are so long that the waterbuses could not be used

by commuter traffic:

Tollcross

is the original eastern terminus of the Union Canal, on the site of

Fountainbridge Brewery.

The terminal is ¼ mile from Lothian Road and

¾ mile from Princes Street.

It is also close to recently built office blocks and

to the Edinburgh Stock Exchange.

Fountainpark

is an area given over to entertainments like cinemas and restaurants,

functioning as a community hub.

There is a large pedestrian square here with pubs, restaurants, a cinema and

other amenities, as well as a walkway to Dalry Road. Haymarket Station and tram stop

are just under one mile from Fountainpark.

There are a number of student residences at Fountainpark.

Harrison Park

is a recreation ground. There are public facilities for servicing

narrowboats at the western end of the park, adjacent to the canal. Harrison Park

is just over half a mile from Heart of Midlothian football club.

Colinton Road

is intended to serve Craiglockhart, Morningside and Slateford in suburban

south Edinburgh.

This boarding point also offers an interchange with buses 18, 27 and 45.

Longstone boarding point is at the western end of the Slateford

Aqueduct, which is one of the more impressive features of the Union Canal.

The boarding point also offers a stairway down to the Water of Leith Centre

and the Water of Leith path.

Kingsknowe

is next to Kingsknowe railway station.

The railway crosses the canal just east of Kingsknowe boarding point.

The boarding point also serves Kingsknowe golf club

and is half a mile from the cyclepath from Redhall to Balerno.

West Side Plaza

boarding point is 350 yards from West Side Plaza, which

is a dreadful 1960s shopping precint with a bus station, a cinema and a

public library.

West Side Plaza is in the middle of Wester Hailes, an area of

system built blocks of flats erected in the early 1970s.

There is unlikely to be much commuter traffic to Edinburgh from West Side

Plaza

because the bus services are excellent and the journey by water-bus

takes about an hour.

There is also a railway station close to West Side Plaza. It is on the

Shotts line. Kingsknowe station is on the same line and is closer to the

canal.

Sighthill

is an industrial area which includes several large workplaces

and Hermiston Gait

[sic]

shopping centre.

There is a tram stop at Hermiston Gait.

This boarding point is 1¼ miles from Heriot Watt University.

If there turned out to be a demand from students for daily travel

between the student residences at Fountainpark

and Heriot Watt University,

a boarding point could be added at Hermiston House Road,

¾ mile from the university.

Ratho

is a village on the outskirts of Edinburgh.

This boarding point also serves Newbridge industrial estate,

which might generate some commuter traffic.

Climbing Arena

is close to the Edinburgh International Climbing Arena, which would

generate some leisure traffic. The Climbing Arena is also very busy on

those days when it is used to host competitions.

Clifton Road

serves Clifton Hall School

which might generate some school traffic and some leisure traffic.

This boarding point is just over half a mile from the western edge of

Newbridge Industrial Estate and might generate some commuter traffic.

M8 Park and Sail

was an attempt to provide an interchange between the waterbus route and the M8 motorway,

which crosses the canal just south of Broxburn.

Building this boarding point requires the construction of about half a mile of slip roads,

as the nearest exit from the motorway is at Newbridge.

This boarding point would allow convenient access from the motorway to the canal, which

would benefit tourist traffic travelling by car from outside Edinburgh.

Port Buchan

is the western terminus of the passenger service.

It is a quaint canal basin in Broxburn, a former industrial suburb

to the west of Edinburgh. Broxburn is a residential district, but East Mains

Industrial Estate is one mile to the east and Houston Industrial Estate

is 2¾ miles to the west.

a.

that there were two mooring areas

for waterbuses, one at each end of the route,

a.

that the first journey from Port Buchan to Edinburgh should arrive in time for

commuters to travel to work,

c.

that there should be an interval schedule throughout the day.

First

Last

First

Last

Port Buchan

05:00

21:00

Tollcross 05:30 21:30

M8 Park and Sail

05:18 21:18

Fountainpark 05:35 21:35

Clifton Road

05:43 21:43

Harrison Park 05:44 21:44

Climbing Arena

06:00 22:00

Colinton Road 05:51 21:51

Ratho

06:14 22:14

Longstone 06:04 22:04

Sighthill

07:04 and 23:04

Kingsknowe 06:14 and 22:14

West Side Plaza

07:15 hourly 23:15

West Side Plaza 06:27 hourly 22:27

Kingsknowe

07:29 until 23:29

Sighthill 06:39 until 22:39

Longstone

07:39 23:39

Ratho 07:29 23:29

Colinton Road

07:52 23:52

Climbing Arena 07:43 23:43

Harrison Park

07:59 23:59

Clifton Road 08:00 00:00

Fountainpark

08:08 00:08

M8 Park and Sail 08:24 00:24

Tollcross

08:13 00:13

Port Buchan 08:43 00:43

For a start,

in order to arrive in Tollcross

before 08:30

it is necessary to leave Port Buchan at around 05:00.

Since a bus journey from Broxburn to Princes Street takes 45 minutes, it seemed

unlikely that a waterbus would turn out to be a convenient way of getting to work.

But, worse, it takes all but eight hours to make a round trip from Tollcross back to

Tollcross, or from Port Buchan back to Port Buchan.

Since each bus takes 3¼ hours

to make a on waay trip, an hourly service needs twelve buses, each with a crew of two

or, more likely, three. and working time regulations would limit each crew member to

about 40 hours’ work per week.

Driving public transport is a strenuous job.

A Commons debate on 6 June 2019 (see Hansard, Volume 661, Column 184WH)

heard that about 40% of bus drivers work

more than 90 hours per fortnight.

If we accept 40 hours as the crews’ maximum working week, then a

crew can only work one eight-hour return trip per day.

The cost of a 28 seater waterbus is estimated at £95,000,

which is the price of a low end single decker road bus.

The cost is equivalent to an annual payment of £11,000 at 3% interest.

Crew are estimated to cost £26,000 salary p a.

So the cost of running a waterbus service of this frequency is about £1·6 M

per year.

So, having ruled out providing an hourly service calling at all boarding points,

I have to consider instead the possibility of serving the tourism industry.

That means providing at most three services in each direction in the middle

of the day in summer when the Edinburgh Festival is operating, and

one service in each direction per day during the shoulder season.

If the traffic available is tourist traffic, then the facilities on the boats

have to be of a high enough standard to attract tourists and holiday-makers.

That probably means hot food and sales of licensed drinks.

The problem is that because of its design, following the 240 ft contour,

the Union Canal doesn't really go anywhere except from Falkirk to Edinburgh.

Although the canal runs through the middle of Polmont and Linlithgow,

the towns and suburban centres

of western Edinburgh do not lie along the canal.

That, of course, can be seen as poor urban planning. Where transport routes

exist, it would have made sense to site trip generators along them.

It would be easier to provide public transport instead of catering for

the endless use of cars

if airports, cinemas, parks, hospitals, housing estates, industry,

office blocks, schools, supermarkets and so forth were located along

roads, railways and canals instead of being plonked onto green-field sites

miles from the nearest railway station.

In Edinburgh even such large trip generators as Edinburgh Airport,

the Western General Hospital, Hermiston Gait shopping centre and

Heriot Watt University were not sited near railway lines, and bus and

tram stations have had to be provided for them.

The target to beat is a journey time from London to Birmingham, 101 miles, of 52 minutes,

since that is the expected journey time on HS2. That would require an average speed

of 117 mph.

Trains can only accelerate gently, at a maximum of 0·1 g

(3·2 ft.sec⁻²,)

otherwise any standing passengers will fall over and hurt themselves.

Therefore the maximum speed has to be appreciably higher than the average speed.

You need a maximum speed of 175 mph to travel 101 miles from a standing start to

a standing finish in 52 minutes.

The target to beat is a journey time from London to Birmingham, 101 miles, of 52 minutes,

since that is the expected journey time on HS2. That would require an average speed

of 117 mph.

Trains can only accelerate gently, at a maximum of 0·1 g

(3·2 ft.sec⁻²,)

otherwise any standing passengers will fall over and hurt themselves.

Therefore the maximum speed has to be appreciably higher than the average speed.

You need a maximum speed of 175 mph to travel 101 miles from a standing start to

a standing finish in 52 minutes.

These are back-of-a-fag-packet figures, but we live in a world where

any estimate of costs is considered better than none.

(Ask Diane Abbott if you don't believe me.)

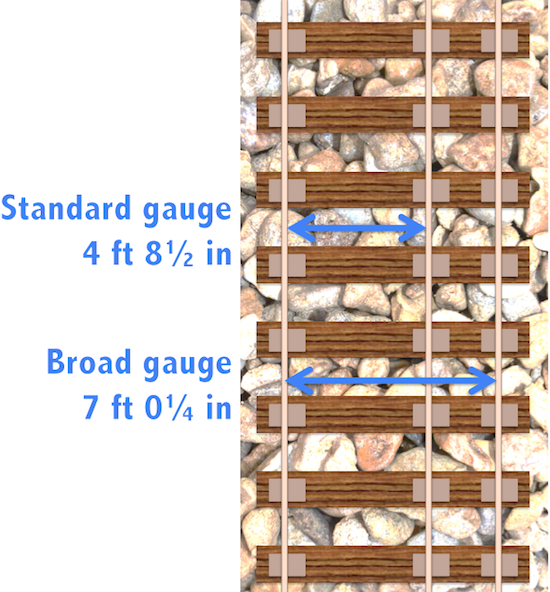

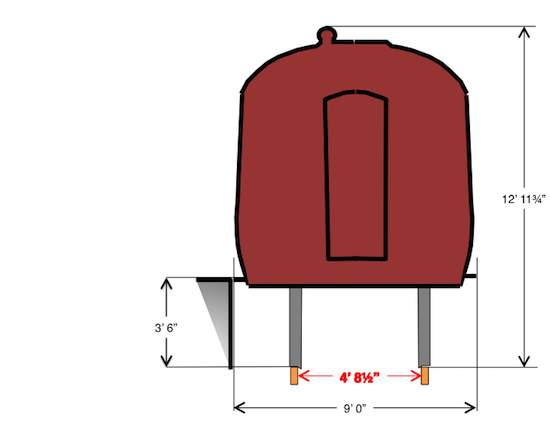

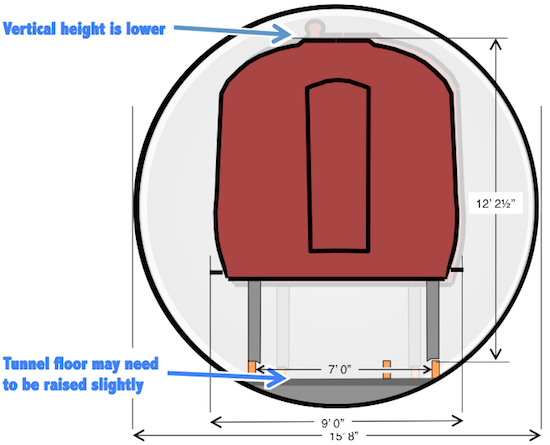

In general there is very little

land purchase cost, because the broad gauge track is achieved by

dual gauging existing standard gauge track and keeping down the cost of

re-building gantries, tunnels and bridges by designing broad gauge trains

to fit within the present standard gauge clearances.

These are back-of-a-fag-packet figures, but we live in a world where

any estimate of costs is considered better than none.

(Ask Diane Abbott if you don't believe me.)

In general there is very little

land purchase cost, because the broad gauge track is achieved by

dual gauging existing standard gauge track and keeping down the cost of

re-building gantries, tunnels and bridges by designing broad gauge trains

to fit within the present standard gauge clearances.