A Train for Very Rich Passengers

According to

this news story,

residents of the town of Farnborough,

a small village in southern England and officially a district of Greater London,

are pretty tired of the constant noise that issues from their local airport.

Yet here, the story takes an unexpected turn.

Farnborough does not have an airport. That is, it has an airport,

but not one that most of us could use, even if we had to get to Farnborough in a tremendous hurry. Farnborough Airport is for VRPs only. Very Rich Passengers. Only private planes use it.

It seems that the market for astronomically expensive travel is expanding, and for that reason, to the chagrin of all who live below their flight path and believe that bus fares are far too expensive, Farnborough Airport is planning to increase the number of week-end and Bank Holiday flights from 8,900 per year to 13,500, half as many again. Which, of course, is why the residents of Farnborough are terrified of the racket that is to come.

Britain is a small and crowded island, and perhaps private aeroplanes are not the best way for people, even VRPs, to get around. I suggest that we should bring back the private train.

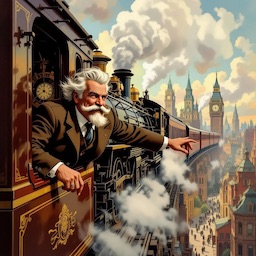

In the nineteenth century, numerous rich people owned their own trains and used them to travel anywhere they wanted. In recent years the only remaining privately owned trains, so far as I know, have been those operated for the entertainment of railway enthusiasts. Billionaire Jeremy Hosking owns the rake of carriages that used to form the Caledonian Sleeper, and the Royal Family still has a private train, but it will be decommissioned in 2027.

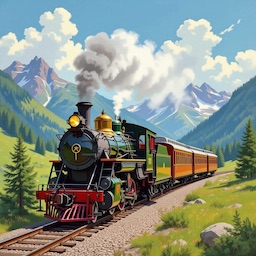

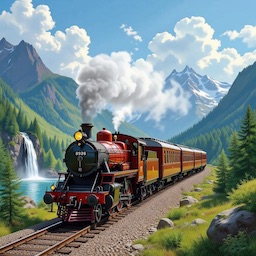

So, forget about private aeroplanes. They are just so last century. Let us bring back the private train. Even more expensive than a private jet, it is a stylish and moderately useful status symbol. Let the homes of the super rich and the places to which they travel be served by spurs of track from the nearest main line. In place of the unbearable noise from one jet engine after another passing overhead, let’s hear the rumble of diesel engines or, even better, the slow chuff, chuff, chuff of steam locomotives hauling their carriages away from the VRP Only platforms immediately outside the football grounds and the concert halls and the nightclubs where their super-rich owners perform.

Of course we shall also need VRPs Only railway stations in our principal cities, and such stations still exist in various stages of disintegration. If only they hadn’t demolished Broad Street and Kings Cross York Road, they would have been ideal VRP Only stations serving the north of the city of London. The former international platforms at Waterloo could still form a VRPs Only station serving the south of London.

Of course, rebuilding those stations would be expensive, and so would laying down the tracks to the venues of various events and to some expensive houses, but the government tends to have money lying around for the transport of rich people: remember Concorde and the Queen Elizabeth 2. It is everyone else whose train and bus services are a luxury in which the taxpayer can no longer afford to indulge.

It would be a useful side effect of this renovation programme that new buildings would be built closer to railway stations than they are now, making travel easier for everyone.

A private train costs about £5 million, not including all the fittings and furnishings necessary to turn it into a mobile home, office, bedroom and performance space with room for a crew of three or four. What’s more, if the figures from the Royal Train are roughly correct, it costs about four times as much to travel in a private train as it does to travel in a private jet. That means that for a VRP looking to display his wealth and social status rather than actually to go anywhere, a private train, and travelling on it, is a very effective status symbol — and, unlike an aeroplane, if you paint your name in big letters on the side of a train, everyone along the route will be able to read it.

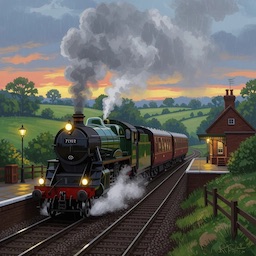

Of course, my purpose in writing this post is not just to make a suggestion that would save the ears of Farnborough’s residents a good deal of splitting. It is also an excuse for drawing some pictures. Here are the pictures: click on them to see the full size versions.

![]()

You can have luxury, but it has a price tag:

Fares on the famous Brighton Belle were higher than ordinary fares on the same route

Broad Street station in the City of London, now demolished

King’s Cross York Road station, now derelict

The international platforms at Waterloo, still intact but put to another use